With more than 200,000 victims of the internal armed conflict (1960-1996), including around 45,000 disappeared, the great majority at the hands of government forces, Guatemala has largely failed to address the issue of the Missing. For the families of the dead and the missing the prospect of achieving justice, including ascertaining the facts and circumstances of their death and accountability for those responsible, is very limited. Since the conflict ended, the failure of former governments to address opposition, corruption, and security issues has impeded human rights investigations, making the work of finding and identifying victims of enforced disappearance challenging. Some 18% (over 8,000) of the Missing have been found, with positive identification of about half, 83% of whom are – according to the Commission for Historical Clarification (CEH) – from Indigenous communities.

Many perpetrators have enjoyed de facto impunity, and many continue to hold positions of power, insulated from prosecution by a lack of judicial independence and an Attorney General who is loyal to the abusing regime, causing many cases to be dismissed on technicalities. While former military dictator General Efrain Ríos Montt was indicted for genocide and convicted in 2013, the sentence was overturned, and his retrial had not been completed when he died in 2018. Another former military dictator, General Fernando Romeo Lucas García, died in Venezuela in 2006, months after a request for extradition by the Audiencia Nacional of Spain, in order to take him to trial for torture and genocide, had been denied.

In the absence of political will, there is still no national mechanism with a mandate to search for the bodies of the Missing. A draft missing persons law was initiated but did not pass congress. While state institutions, including the INACIF (Instituto Nacional de Ciencias Forenses) have capacity to recover bodies and evidences for forensic cases, they had, until recently, avoided processing cases of the internal armed conflict. They have no capacity to undertake exhumations, forensic anthropology and genetic analysis at the scale required to recover and identify the Missing. Searches and exhumations have instead been conducted by civil society bodies such as the Fundación de Antropología Forense de Guatemala (FAFG), operating under formal court and prosecutor orders. Evolving to become an intrinsic part of the national effort to provide evidence and truth to victims’ relatives and communities, FAFG have developed effective investigation practices over time to recover the Missing, thereby allowing families and communities to bury their repatriated dead according to their traditions.

In 2002, FAFG implemented the ‘Officialization of the Manual of Procedures for Forensic Anthropological Investigations in Guatemala’ working with the Public Ministry in a new investigative exhumation process. In 2008 they opened their forensic laboratory to undertake DNA testing, and in 2009 published the ‘Searching for Disappeared Persons Manual’. They have undertaken investigations at more than 50 military bases, utilising drones to take multispectral imagery and LiDAR to locate graves, as well as undertaking wider searches across landscapes related to numerous massacres.

From 2012 FAFG experts began to testify in the national judicial process against former regime members charged with genocide and crimes against humanity, using evidence based on their case reports. Court cases have continued to face issues. There are ongoing attempts to delay prosecutions, and challenge laws, for example a failed attempt in 2015 to remove Article 8 of the 1996 National Reconciliation Law, which strips amnesty from officials accused of genocide, torture, or forced disappearance. To date, convictions have mainly been confined to some lower rank perpetrators, with others including senior leaders continuing to evade accountability. In the 2018 trial related to the 2018 Military Zone 21 CREOMPAZ case, only nine of an original 40 indicted perpetrators were jailed, and then given early release in 2024. Though the court in another 2018 case unanimously found that the State of Guatemala – specifically the Guatemalan army – committed genocide and crimes against humanity against the Maya Ixil population under Rios Montt (1982-1983), only one accused was found guilty.

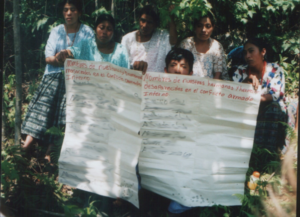

In 2024, FAFG continued providing expert evidence on the Ixil genocide, including the identification, statistical analysis of trauma and cause of death of 588 victims from 112 graves in the Ixil Triangle, recovered between 1998 and 2018. In the villages of Chisis and Quisis alone, 11 graves containing 30 victims were excavated. Ian Hanson, who assisted with the Chisis and Quisis excavations, noted the importance that FAFG give to victims and their families, and that communities place on participating in the work. Many of the victims had been buried by members of their community who returned to villages after fleeing during the 1982 attacks. The communities were therefore integral to not only pinpointing graves but provide evidence.

“The gathering of families and communities to help locate graves, were also opportunities to provide witness evidence to FAFG, to mourn and undertake ceremonies for the victims at the graveside, and also to publicly bear witness to the Missing.”

The court case against former chief of staff of the Guatemalan army, General Benedicto Lucas García (brother of the military dictator), was suspended for alleged court bias amid outcry from survivors and human rights bodies, with the court of appeals to determine a retrial date. While Lucas García and others remain in jail convicted in 2018 for the crimes against humanity of forced disappearance and aggravated rape in the separate Molina Theissen case, their defence teams are appealing, the hearing held on February 6th, 2025.

It is hoped the current reformist Arévalo government will expedite the effective investigation of the Missing and the pursuit of accountability against those most responsible, although the experience of the Lucas García case and others suggests that the path to justice for victims will be a difficult one. Claudia Rivera, Director of Forensic Science at FAFG is pragmatic:

“In the current circumstances, court cases are a plus. If convictions don’t happen, families still received their loved ones.”

There is a long way to go to provide truth, justice, and the remains of their loved ones to all the families of victims in Guatemala, but for the families of the Missing the desire for truth and justice remains strong.

The community poster reads “names of our brothers and sisters that disappeared in the internal armed conflict”

The community poster reads “names of our brothers and sisters that disappeared in the internal armed conflict”

Acknowledgements

Thank you to Claudia Rivera and Daniel Barczay of FAFG for their input and comments.