Our pilot began with the a priori knowledge outlined in the Bournemouth Protocol that mass graves are highly context specific and should therefore be dealt with on a case-by-case basis (p.6). An approach that recognised the uniqueness of each mass grave site as opposed to imposing homogeneity, was  crucial. However, of equal emphasis was the need for data comparison, both for the observation of patterns in the data and to ensure an appreciation of the global scale of the issue.

crucial. However, of equal emphasis was the need for data comparison, both for the observation of patterns in the data and to ensure an appreciation of the global scale of the issue.

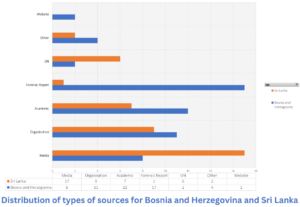

To this end, the contrasting socio-political environments, and the associated quality and quantity of data, led us to apply Sri Lanka and Bosnia and Herzegovina for our pilot. The well-established transitional justice processes in the Balkans have led to a wide-ranging archive of sources that includes comprehensive investigations, documented evidence, and detailed archaeological and anthropological forensic findings. Conversely, the longevity and protracted nature of Sri Lanka’s 30-year conflict has resulted in limited progress in investigating, prosecuting, and providing reparations related to mass graves.

Our approach involved:

- Agreeing on a basic set of data points. The multitude of sources we had available for Bosnia proved an effective way to ‘test’ these categories and make tweaks as needed. In contrast, the lack of information on Sri Lanka allowed us to ensure these data points could be replicated across different kinds of site.

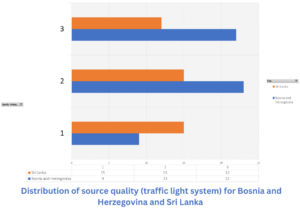

- Developing a ‘traffic light’ system to categorise the quality of sources. Court documents, forensic reports, and official reports from commissions and institutions occupied the highest tier. Academic publications and media reports where at the lowest tier and were used as supplementary sources.

Our pilot revealed a number of findings:

- The availability and accessibility of official reports was, and will continue to be, our main challenge. Our data fields for Sri Lanka were considerably less complete than for Bosnia. Crucial for the research was the knowledge of what data is available, but just difficult to find, and what knowledge is simply unavailable due to the lack of an effective investigation.

- Even when available, inconsistencies between naming conventions, location, data, and categorisation of sites made them difficult to cross reference. This was particularly true in Srebrenica sites in Bosnia, where the practice of exhuming and relocating bodies after initial burial to conceal evidence was common. For forensic archaeologists and anthropologists this meant that the challenge of calculating accurate victim numbers was particularly acute. Due to the involvement of a variety of different organisations in Srebrenica, with different goals and differing categorisation, we found that the data between different reports was often non-comparable.

- Further complicating data inconsistences was the unmarked and remote location of most mass graves. This, in combination with deliberate concealment by perpetrators, presented difficulties for accurate geo-location of sites. For example, in Srebrenica the exhumation and re-burial of remains was common, and in Sri Lanka graves were often hidden under newly constructed buildings or infrastructures.

- This phenomenon also has implications for site protection, return of remains, and commemoration, which we discovered to be lacking in both contexts. In general, we found a paucity of information regarding post-investigation processes, if they existed at all.

Finally, and most significantly, our pilot revealed that progress within transitional justice processes does not necessarily reflect progress on the ground. Resultantly, it was imperative that our methodology captured the correlation between the variability of factors that lead to the creation of mass grave sites, and the resulting disparity between disciplinary and institutional expertise that governs inconsistent degrees of protection, investigation, and engagement of sites. In Sri Lanka, mass graves serve as part of a wider apparatus of terror; through dismissal of inquiries, intimidation of officials and victims’ relatives, and corruption, the state continually reaffirms and reproduces its domination. In Bosnia and Herzegovina, despite extensive forensic investigations, exhumations, DNA identifications, and ultimately prosecutions, the country remains deeply divided and genocide denial and historical revisionism of the Srebrenica genocide is on the rise.

Mass graves, and their investigations, are both inherently complex and highly politically contentious. They transcend the often-narrow categories of transitional justice, and reveal overlooked and unforeseen social, sectarian, economic, and political complexities. It is precisely for this reason that an effective mechanism for their capture and comparison is needed, as Dr Agnes Callamard, UN Special Rapporteur on Extrajudicial, Summary or Arbitrary Executions states in the preface to the Bournemouth Protocol (p.4) “all have important stories to tell- truths that often have been left untold, denied, covered up or buried.”

Ellen Donovan and Diego Renato Nunez