MaGPIE’s mass grave mapping comprises multiple steps; searching for and categorising mass graves, deciphering the relevant treaties, laws, and institutions each State uses to address them, investigating the best forensic investigation practices, and determining how justice can be achieved for the victims, families and affected communities.

Dr Ellie Smith focuses on the latter aspect—achieving justice in the aftermath of atrocity. Investigating a mass grave, as described by Dr Ian Hanson, aims to reveal the complex facts surrounding those discovered. However, investigations have the equally important effect of enabling the pursuit of justice, not only for those discovered, but for those left behind. Families and affected communities are often agonisingly searching and waiting to learn the fate of their loved ones, and when their graves are finally excavated, justice can be sought in the manner of the ‘right to the truth’, shining a light on the exact nature of their loved one’s death. Effective justice mechanisms also include understanding the bigger picture that resulted in their ‘missingness’ and seeking avenues for redress. A comprehensive, qualitative understanding of what justice measures are available to, and have been received by victims in relation to mass graves, is of great utility. It offers crucial insights for the development of a much-needed and nuanced appreciation of justice requirements with clear potential for victim-responsive policy and practice. While it might seem inevitable that the discovery, excavation, and return of human remains from a mass grave would lead to trials and prosecutions, this is not always the case. Even when States do have mechanisms in place, whether they are widely utilised, or result in justice for the families and loved ones, is another matter entirely.

Justice measures, and their effectiveness, cannot be understood in a vacuum, and thus the case study countries being undertaken are the same as those selected for Dr Ian Hanson’s effective investigation workpackage. These are; Guatemala, Bosnia and Herzegovina, Iraq, Cambodia and Rwanda – such spread accommodates varying contexts and thus varying investigation and justice outcomes.

Both Bosnia and Herzegovina and Guatemala are currently being worked on in tandem, Bosnia to correlate with work being undertaken by Dr Ian, and Guatemala because of the recent MaGPIE country visit. As expected, these countries are providing very different results.

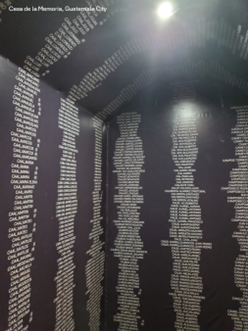

Despite the sheer scale of violations  and the fact that the conflict effectively devastated Bosnia’s infrastructure – including overwhelming its court system – activities aimed at the investigation and prosecution of perpetrators are ongoing, albeit with relatively low prosecutions rates. By contrast, and within a context of official denial, inaction and antagonism, prospects of pursuing and achieving justice in Guatemala are very low, and work on locating the missing, and victim memorialisation, is conducted by victims’ families, victim groups and NGOs. In both countries, there is a widespread perception of impunity, and perpetrators remain in positions of power. Their criminal justice systems are hampered by a lack of resources for both legal and forensic functions, and significant political interference – probably more so in Guatemala but increasingly in Bosnia, and especially in the Republika Srpska, where ethnic tensions, nationalism and genocide denial are on the rise. In both cases, witnesses are unwilling to come forward, and suffer threats and intimidation.

and the fact that the conflict effectively devastated Bosnia’s infrastructure – including overwhelming its court system – activities aimed at the investigation and prosecution of perpetrators are ongoing, albeit with relatively low prosecutions rates. By contrast, and within a context of official denial, inaction and antagonism, prospects of pursuing and achieving justice in Guatemala are very low, and work on locating the missing, and victim memorialisation, is conducted by victims’ families, victim groups and NGOs. In both countries, there is a widespread perception of impunity, and perpetrators remain in positions of power. Their criminal justice systems are hampered by a lack of resources for both legal and forensic functions, and significant political interference – probably more so in Guatemala but increasingly in Bosnia, and especially in the Republika Srpska, where ethnic tensions, nationalism and genocide denial are on the rise. In both cases, witnesses are unwilling to come forward, and suffer threats and intimidation.

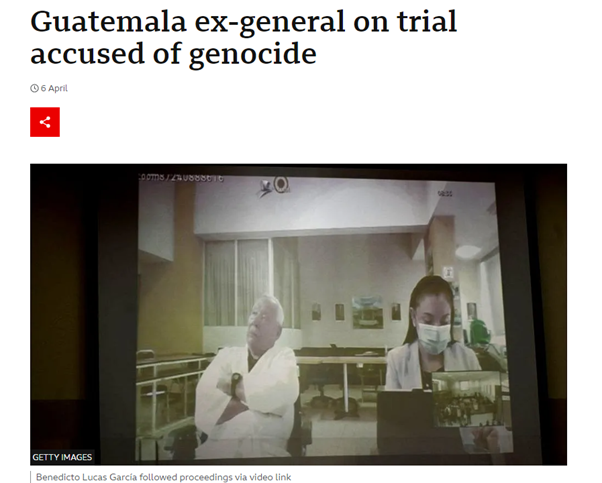

I nternational courts have provided justice for some survivors in a number of cases, although in neither instance are they equipped to deal with the very large number of victims involved, and in the case of the International Criminal Tribunal for the Former Yugoslavia (ICTY), only those deemed to be most culpable for crimes are prosecuted, and reparations cannot be awarded. With a new president elected on an anti-corruption platform, Guatemala is now witnessing the domestic prosecution of a former army general for the crime of genocide, sparking hope for families that justice will finally be forthcoming, but in the case of both countries, as both perpetrators and witnesses age, the opportunities for justice will become less and less.

nternational courts have provided justice for some survivors in a number of cases, although in neither instance are they equipped to deal with the very large number of victims involved, and in the case of the International Criminal Tribunal for the Former Yugoslavia (ICTY), only those deemed to be most culpable for crimes are prosecuted, and reparations cannot be awarded. With a new president elected on an anti-corruption platform, Guatemala is now witnessing the domestic prosecution of a former army general for the crime of genocide, sparking hope for families that justice will finally be forthcoming, but in the case of both countries, as both perpetrators and witnesses age, the opportunities for justice will become less and less.

Dr Ellie Smith